This report is based on a presentation given to the Chartered Institute of Accountants of Australia and New Zealand in April 2023. Statistics and opinions are correct at the time of writing.

We cannot have infinite growth on a finite planet. Decades of living in a society where waste is someone else’s problem means that countries around the world have generated huge landfill sites – and the rubbish dumped at those sites has been steadily releasing greenhouse gases into our atmosphere.

This, of course, has contributed to an acceleration in the planet warming, and to what we now rightly call the Climate Emergency. And it’s still happening. Even when we think we are sending waste to recycling or reuse plants, it can still end up in landfill.

In fact, according to RMI, a long-established non-profit organisation working towards a zero-carbon future, in 2020 20% of all human-related methane emissions stemmed from municipal solid waste and waste water. That makes waste the third largest polluter, after enteric fermentation and oil and gas.

This isn’t sustainable on any level. Practically, we can’t keep creating new landfill sites or adding our waste to existing sites. There’s not enough room, and the consequences for our planet are dire. We need to dramatically change the way we think about and manage waste, aiming for zero waste to do our bit to reach zero emissions.

At the bottom of the pile

If waste is such a massive contributor to the climate emergency, why don’t we hear more about it?

I think it’s because it’s far more exciting to talk about electric cars, offshore wind farms, solar panels, nuclear fusion and carbon capture. These are ‘things’ that people can hang their hats on.

What’s forgotten, of course, is that ALL these sexier things create significant amounts of waste. And that’s hardly ever mentioned. As always, waste ends up at the bottom of the pile.

What can we do to change the way we think about waste? We need to take dramatic steps now if we are to effect the changes we need to make.

What does the law say?

There’s been no shortage of legislation and commitment. In 2016, the Paris Agreement was hailed as a momentous moment for climate control. Attendees signed to say that global warming should be limited to 1.5°.

At that point, most people thought we had years to get to that point. But climate change has accelerated faster than predicted, and according to the United Nations, there’s a 50:50 chance of average global temperatures reaching that limit by 2027.

We haven’t got long.

In the UK, the Environmental Act of 2021 claimed to be ‘the most ambitious environmental programme of any country on earth.’ It included the following goals:

- Extended producer responsibility to make producers pay for 100% of cost of disposal of products

- A Deposit Return Scheme for single use drinks containers

- Charges for single use plastics

- Greater consistency in recycling collections in England

- Electronic waste tracking to monitor waste movements and tackle fly-tipping

- Tackle waste crime

- Power to introduce new resource efficiency information (labelling on the recyclability etc.)

- Regulate shipment of hazardous waste

- Ban or restrict export of waste to non-OECD countries

This legislation does have teeth. The Extended Producer Responsibility requirements have come into force. There’s more power to tackle waste crime like fly tipping. And the UK has cut back on sending waste to developing countries.

All of this is good news – the will to deal with waste at the ‘waste’ end of things is there. But we need to tackle it from the beginning of the production cycle too. In order to reduce waste, we must rethink everything.

The circular supply network

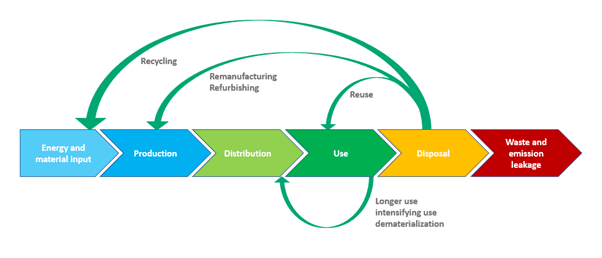

Reducing waste starts with not using new resources. It starts with looking at designs and manufacturing capabilities and saying: ‘how can we make our product without mining new resources? What can we change so we can use recycled or reusable materials? How can we manage our production so it uses less energy, is more energy efficient, or is driven by renewable energy? How can we make sure we don’t leach harmful substances into the ground or waterways? How do we make sure that people can repair or reuse our product rather than throwing it away? And how do we help people dispose of the product safely and with as little waste as possible?

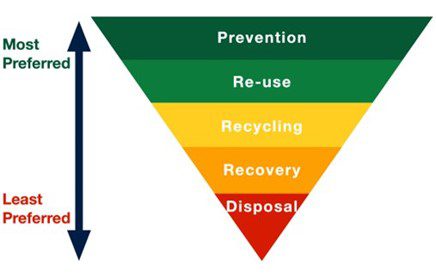

All difficult questions. And all with commitment and cost associated with them. This is where it’s simplest to look at the Waste Hierarchy model:

The more we can concentrate on the top end of this model, the better results we’ll achieve.

For example, composting can make a huge difference at the re-use/recycling point. A report by the UN and Climate and Clean Air Coalition found that waste sites could but methane emissions by up to 35% just by reducing the organic waste sent to landfill sites.

And, of course, getting better at separating, segregating and recycling redundant materials will ensure less goes into landfill and more is put back into the economy. This leads to a zero-waste approach – something we have to do if we want to make a difference.

Improving existing landfill sites

Of course, it’s easy to say: ‘Let’s start doing things differently’. We also need to consider what to do with the billions of tonnes of waste sitting in landfills right now. Is there any way to reduce their long-term impact?

Landfill mining is an option here. Essentially, mature landfill sites can be ‘mined’ to extract materials that can be reprocessed or recycled. Hazardous materials can also be taken away and properly disposed of, reducing the risk of leaks or spillage into the soil and the air.

This is an expensive business, however, so there needs to be the financial support for it, as well as the environmental will. It is happening, however, and the industry is calling for economic incentives to make it a cost-effective and realistic option.

An economic argument

Better waste management isn’t just about doing things better. It’s about taking advantage of the economic opportunities it presents.

For example, the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) reported that in 2015, greenhouse gas emissions from plastics were 1.7 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent; by 2050, they’re projected to increase to approximately 6.5 gigatonnes. That number represents 15% of the whole global carbon budget – the amount of greenhouse gas that can be emitted, while still keeping warming within the Paris Agreement goals. UNEP added that in 2021, plastic accounted for 85% of all marine litter. It predicted this will triple by 2040, adding up to 27 million metric tonnes of plastic waste into the ocean every year.

And that’s just the plastic that ends up in our waters. Around 50% of plastic still goes to landfill. And we’re not showing signs of slowing our use of this material.

So we need to treat it differently. For example, in Kenya, there’s a plant that receives plastics from local landfills and waste collections. The plastics are shredded, heated at high temperatures and turned into industrial oil. 12 tonnes of plastic produces around 7,000 litres of oil.

Businesses like these provide employment, contribute taxes and help to remove plastic from the waste cycle. A clear economic benefit from a green business opportunity.

And there are many more of these opportunities around, if only we have the vision to take them.

Where do we go next?

Like most systematic change – and no change has every required commitment on a global scale – moving to a zero-waste economy simply won’t happen unless we make it happen.

In fact, we are going to have to face some uncomfortable truths and take complete responsibility for what we throw away.

At ISB Global, we support a global push for a ‘Pay As You Throw’ model. What does this mean? It means we charge people for adding to the waste problem. In practical terms, the most likely way to manage this model is:

- We pay for our waste containers, bags, wheelie bins, which are all tagged

- The tag links the container to the relevant person or company, and the waste designated for that container

- Every collection vehicle has RFID/NFC readers, with cameras and onboard weighing

- Every collection creates a charge (or a rebate), based on the material type/weight

- Cameras/AI catch those trying to put material in the wrong bin

- All tags must be pre-paid, otherwise the truck will put the container back down

We must enact complete behaviour change in this area – it’s the only way to reduce the impact of waste in time to have a measurable effect on greenhouse gas levels.

Supporting the waste industry to change

Of course, in order for this radical approach to work, waste and recycling management companies have to be able to manage the technology and process the waste. Whether that’s to recycling plants, to secondary markets or to reuse opportunities, they need to have the systems and approaches that will support consumers and businesses to meet their waste requirements.

That’s our focus at ISB Global, and it’s why we’ve developed Waste & Recycling One (WR1). This unique technology solution replaces outdated legacy systems, creating a single, central source for data and processes. It can help waste companies to meet legislative requirements, reduce costs, improve efficiencies and play a leading and significant role in the next – and fundamentally important – chapter in waste management around the world.